When a mother kills REDUX

Monday, January 11, 2010 at 8:25PM

Monday, January 11, 2010 at 8:25PM I published this in April of last year. I think, as Casey still sits in jail awaiting trial, it is worthy of a second look. I took the liberty to tweak it a little, too.

I resourced a number of clinical studies that are referenced at the bottom. I am not a psychiatrist, nor a psychologist. I have interpolated and interpreted those articles and discussions into one by rewriting and condensing them. Hopefully, this is something more palatable to read and mentally ingest. You can digest it in the privacy of your home or workplace, and you can egest it in the comments section.

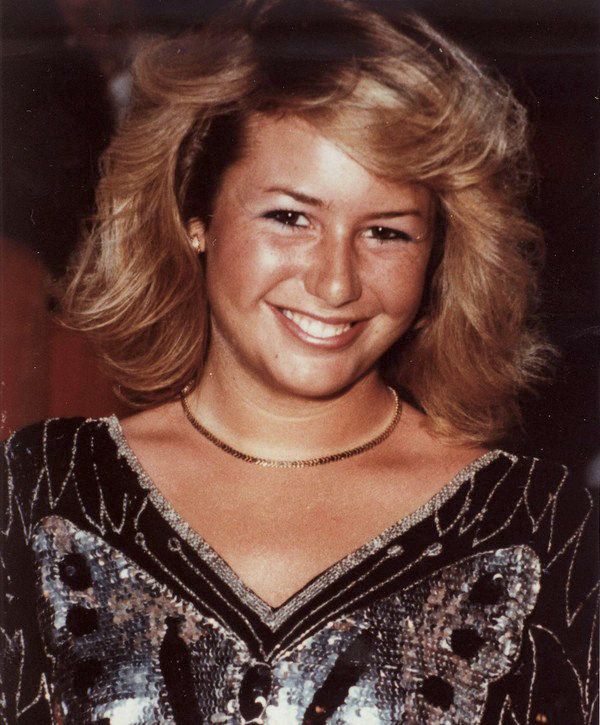

Murder is considered to be an unthinkable crime by most societies on earth, but when parents kill their own children, it rattles and shakes the foundation of humanity. It is the lowest of lows, the worst form of all crimes imaginable. Casey Anthony will go on trial for first-degree murder in the death of her not quite 3 year old daughter, Caylee. If found guilty of the crime, she faces her own sentence of death. This is not intended to place guilt or innocence on her. It is a study in filicide, the murder of one’s own children.

Because of a lack of understanding, most of us are immensely shocked by the pure nature of filicide. Although considered uncommon, it is one of the leading causes of child deaths in civilized societies throughout the developed world. In a 1995 poll taken of 25 countries, it indicated that the homicide rate for children under 1 year old was greater than the rate for adults. Large-scale studies have shown that younger children are most at risk, especially those under 6 months old. After that age, the risk lowers steadily, but increases again in adulthood.

In order to make sense of this crime, large scale population studies of filicidal offenders have been performed and remarkably, rates of infanticide (child murder in the first year of life) parallel suicide rates. Based on their studies, the existence of several groups and classifications have been determined for filicide, and each classification has distinct characteristics and factors that drive parents to kill. Because of these reviews and publications, we will explore the different types, paying particular attention to maternal filicide, which is defined as a child murdered by the mother. My goal is not to elicit sympathy for Casey; it is to offer explanations for why she might have done it. Remember, until a jury decides, she is innocent in the eyes of the law, the only thing that matters. Please bear in mind that in some developing countries, the preference for male children may lead to selective killings. Think China. Religious, cultural and legal differences across borders will vary some of the research findings in some studies. Also, one country’s decision to send someone to prison may be different than another country’s choice to send someone to a psychiatric hospital. Because actions vary greatly, all I ask is that you maintain an open mind. Although specifically dealing with maternal filicide, this article is not just about one person.

CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS

Motive

In 1969, psychiatrist P.J. Resnick looked into 131 case reports from world literature on child murders by both mother and father from the years 1751 - 1967 and wrote his article based on the apparent motives for the acts.The five categories he came up with in this system are “altruistic” filicide (64 cases, 48.9%), “acutely psychotic” filicide (28 cases, 21.4%), “unwanted child”filicide (18 cases, 13.7%), “accidental” filicide (16 cases, 12.2%), and “spouse revenge” filicide (5 cases, 3.8%). Resnick described cases of altruistic filicideas murders committed out of love. The mother believes it is in the child’s best interest. A suicidal mother may not wish to leave her motherless child to face an intolerable world or she feels she is saving the child from a fate worse than death. In acutely psychotic filicide, the parent kills the child under the influence of severe mental illness or a psychotic episode. Here, a delirious mother or psychotic mother kills without any comprehensible motive. It may be merely following a command hallucination to kill. In accidental or fatal maltreatment filicide, death is not the expected outcome. It results from cumulative child abuse, neglect, or Munchausen syndrome. Unwanted child filicide occurs when mothers, for reasons such as illegitimacy or uncertain paternity, kill their child through acts of aggression or neglect. It could also result from a mother thinking of her child as a hindrance. Spouse revenge filicide happens when the mother kills to emotionally harm the child’s father.

Resnick’s review on world psychiatric literature on maternal filicide found most of these mothers to have frequent depression, psychosis, which is a “loss of contact with reality,” prior mental health treatment, and suicidal thoughts.

Impulse to Kill

Although useful, one of the problems with classifying the motives of filicidal parents is that the motive is almost entirely procured by police and forensic psychologists, mostly at a time when the offender is likely to be very vulnerable and highly defensive. The individual is concerned with criminal charges. Some doctors feel a classification based on the origin of impulse to kill is more objective than simply basing it on motive, which may be more subjective, over-determined or defensive. The impulsive system is not widely recognized because it lowers a mother to a primitive level and looks at sophisticated motives such as revenge or altruism as inappropriate.

Because most modern classification systems focus on the characteristics of the female parent, a six-year study was done of 89 women remanded to a prison under the particular charges of murder or attempted murder of their children. In this study, six categories unfolded: battering mothers, mentally ill mothers, neonaticides, retaliating women, unwanted children, and mercy killing. These categories are similar to Resnick’s, with the exception of the exclusion of the “acutely psychotic” classification and the addition of “mercy killing” which is basically nothing more than euthanasia for a sick and suffering child. In the studies, three most common identifiable groups emerged: neonaticides, battering mothers and mentally ill mothers.

CLASSIFICATION SUBGROUPS

Neonaticide

Resnick coined the term neonaticide to describe the killing of a child less than 24 hours old. This group is the most clearly defined and it is the one that mostly differs from the other groups. It is the largest group. Neonaticide is almost exclusively carried out by women. The mothers are younger, rarely married, poorly educated, have a low level of psychiatric disorders and psychosocial stressors, no history of criminal behavior and do not attempt suicide after the murders. They generally do not seek out abortions. They conceal and do not acknowledge their pregnancies and are sometimes motivated by a feeling of shame and guilt because of the fear of child-rearing out of wedlock. So why don’t these women just get abortions? There are major differences between the women who get abortions and those who commit neonaticide, with passivity being the most important separating factor. Most women who commit neonaticide have made no plans for the birth and care of the child and their decisions are primarily based on denial and disassociation.

Accidental Filicide/Battering Mothers

This is the second largest group. Though not as clearly defined as neonaticide, some similarities can be seen. Unintentional deaths result from child abuse. There is no clear impulse to kill, but there is a sudden impulsive act characterized by a loss of temper. In case studies of large groups of filicidal mothers, these mothers suffered the greatest amount of social and family stress, marital stress, and housing and financial problems.

Mentally Ill Filicides

Though the least common, mentally ill filicides are the most complex. The intensity of the suffering perceived in the mother’s delusional state is so great that the murder seems rational to them. Most of these women are older, in their late 20s - early 30s, are generally married, are not under a lot of stress, and their children were older. Because of this, killing a child older than one year indicates a much more profound disruption in emotional or mental status than does the killing of a newborn.

About 10-22% of adult women suffer from postpartum depression within the first year after the baby’s birth. The “postpartum onset specifier” includes fluctuations in mood and a preoccupation with infant well-being that can range from over-concern to delusional, and the presence of delusional thoughts significantly increases the risk to the child. Infanticide is most often associated with postpartum psychotic episodes that are characterized by inner hallucinations that command the mother to kill or that the child is possessed. Severe cases seem to occur in from 1 in 500 to 1 in 1,000 births and the risk increases in women who have experienced prior episodes. Once a woman has postpartum depression, the risk with each subsequent delivery increases 30-50%.

In studies, the majority of mothers had displayed psychiatric symptoms prior to filicide and just under half had previously received in-patient psychiatric treatment. While mentally ill filicidal mothers generally have psychiatric histories, they don’t, as a rule, have any history of child abuse and they usually describe having experienced a clear intention to kill. In all studies, drug and alcohol impairment were rarely seen as a consequence, but that’s not to say that substance abuse did not ever factor in.

METHODS OF KILLING

Methods used by mothers to kill their children differ greatly from most homicides and this is where vast differences in gender occur. In contrast to domestic homicides of adults, women do not use knives or guns to murder their victims. Maternal filicide is usually committed using ”hands on” methods that entail close and interactive contact between mother and child; methods such as shaking, beating, suffocation or drowning, and some indirect methods such as arson or drowning while the child is asleep or sedated. In cases of paternal filicide, fathers are more likely to use methods like striking, squeezing, or stabbing, and they are more apt to use weapons. Suffocation, strangulation and drowning are the most common causes of neonaticides.

Interestingly, drowning was high on the list of methods to kill. So was suffocation. In my fictional account of what may have happened to Caylee, I took drowning into account long before I researched this article. Of course, we are all aware of the (inferred) suffocating duct tape found secured to Caylee’s mouth. (Remember, the jury will decide who put it there.)

GENERAL POPULATION STUDIES OF MATERNAL FILICIDE

If we study the general population of filicidal mothers, we find that they were often poor, socially isolated, full-time caregivers, who were victims of domestic violence or they had other relationship problems and socioeconomic disadvantages. Certainly, Casey had problems with her parents and she had no money of her own. What’s puzzling in her case is that she had no history of abusing her child and by all accounts, seemed to be a devoted mother. Friends and family concur.

Persistent crying or other child factors were sometimes the cause for filicides. Some mothers had previously abused the child, while others were mentally ill and devoted to their child. Neglectful or abusive mothers were sometimes substance abusers and many of them had elements of psychosis, depression, or suicidality, the taking of one’s own life.

PSYCHIATRIC SAMPLES OF MATERNAL FILICIDE

In psychiatric studies, filicidal mothers had frequently experienced psychosis, depression, suicidality, and prior mental health care. Their mean age was in the late 20s range. Some were diagnosed with personality disorders and some had low intelligence. Significant life stresses were often noted. In a recent study of mothers found not guilty by reason of insanity in two U.S. states, it was found that the mothers were often depressed and frequently experienced auditory hallucinations, some of a command type. Over 1/3 of the homicides occurred during pregnancy or the postpartum year. Almost all of the mothers had altruistic or acutely psychotic motives. In New Zealand, a small study that interviewed mothers after their filicides found that psychotic mothers who had committed filicide often killed suddenly without much planning, whereas depressed mothers had contemplated killing their children for lengths of time prior to their crimes.

CORRECTIONAL SAMPLES OF MATERNAL FILICIDE

In prison studies, filicidal mothers were frequently unmarried, unemployed and had limited education and social support. Economic, social, partner relationship problems, primary caregiver status and difficulty caring for the child were frequently mentioned as causes. Let me ask you, does this sound like anyone you’ve read about lately, someone who will may be added to this list?

CONCLUSION

In closing, let me say that there are other factors involved in maternal filicide and to go deeper than I have here would be boring and somewhat senseless because they are not really related to the Casey Anthony story. Areas of study include more in-depth looks at previous psychiatric symptoms, intrapsychic processes that include delusions, environmental stress and social isolation. I can’t justify taking up any more of your time, but I may offer another post on the legal process and how we may predict it.

In spite of large scale and individual case studies, filicide will always remain one of the world’s most reprehensible offenses. Cases like Casey Anthony and her daughter continue to shock and awe communities and nations, especially when there are seemingly no salient reasons for the offense. While these studies have revealed several groups, patterns and risk factors, prediction - even by the closest of friends and relatives - is extremely difficult, no matter how much knowledge and organization has been gained. Where you may have a proclivity to blame Casey’s parents for her outcome, please understand that many underlying and complex factors are at play that go completely unnoticed. There is much more to a filicide than casually placing blame on someone else, especially if you have no understanding or training of the psyche of the human mind. If you had any trouble deciphering some of the above psycho-babble, there’s a reason for that. It means I did my job, because as much as you may think you know about Casey’s mind, you don’t. Don’t worry, neither do I.

References:

Cylc, Linda, Classifications and Descriptions of Parents Who Commit Filicide, Psychology, Villanova University

Friedman, Susan Hatters and Resnick, Phillip J. Child murder by mothers: patterns and prevention, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Hanna Pavilion, University Hospitals of Cleveland

Supplemental References:

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition, text revision).Washington, D.C.: Author.

Cheung, P.T.K. (1986). Maternal filicide in Hong Kong. Medicine, Science, and Law, 26,185-192.

D’Orban, P.T. (1979). Women who kill their children. British Journal of Psychiatry, 134, 560-571.

Gold, L.H. (2001). Clinical and forensic aspects of postpartum disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law, 29, 344-347.

Hausman, K. (2002, December 20). Classification tries to make sense of often inexplicable crime. Psychiatric News, 37(24), 14.

Marleau, J.D., Poulin, B., Webanck, T., Roy, R., & Laporte, L. (1999). Paternal filicide: A study of 10 men. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 44, 57-63.

McKee, G.R. & Shea, S.J. (1998). Maternal filicide: A cross national comparison. Journal Of Clinical Psychology, 54(5), 679-687.

Palermo, G.B. (2002). Murderous Parents. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 46(2), 123-143.

Pitt, S.E. & Bale, E.M. (1995). Neonaticide, Infanticide, and Filicide: A review of the literature. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law,23, 375-386.

Resnick, P.J. (1969). Child murder by parents: A psychiatric review of filicide. American Journal of Psychiatry, 126, 73-82.

Resnick, P.J. (1970). Murder of the newborn: A psychiatric review of filicide. American Journal of Psychiatry, 126, 58-63.

Stanton, A. & Simpson, J. (2000). Maternal filicide: a reformulation of factors relevant to risk. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 10,136-147.

Stanton, J., & Simpson, A. (2002). Filicide: A Review. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 25, 1-14.

Stanton, J., Simpson, A., & Wouldes, T. (2002). A qualitative study of filicide by mentally ill mothers. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(11),1451-1460.

Bureau of Justice Statistics, US Department of Justice. Homicide trends in the United States: infanticide.www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/ homicide/children.htm.

Lester D. Murdering babies: a cross-national study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1991;26:83–88.[PubMed]

Marks MN. Kumar R. Infanticide in England and Wales. Med Sci Law. 1993;33:329–339. [PubMed]

Brookman F. Nolan J. The dark figure of infanticide in England and Wales: complexities of diagnosis. J Interpers Violence. 2006;21:869–889. [PubMed]

Zawitz MW. Strom KJ. Firearm injury and death from crime, 1993- 97. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2000

Finkelhor D. The homicides of children and youth: a developmental perspective. In: Kantor GK, Jasinski JL, editors. Out of the darkness: contemporary perspectives on family violence. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1997. pp. 17–34.

Emery JL. Child abuse, sudden infant death syndrome, and unexpected infant death. Am J Dis Child.1993;147:1097–1100. [PubMed]

Ewigman B. Kivlahan C. Land G. The Missouri child fatality study: underreporting of maltreatment fatalities among children younger than five years of age. Pediatrics. 1993;91:330–337. [PubMed]

Resnick PJ. Murder of the newborn: a psychiatric review of neonaticide. Am J Psychiatry. 1970;126:58–64.

Friedman SH. Resnick PJ. Neonaticide: phenomenology and prevention. Int J Law Psychiatry. in press.

Resnick PJ. Child murder by parents: a psychiatric review of filicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1969;126:73–82.

Hesketh T. Xing ZW. Abnormal sex ratios in human populations: causes and consequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13271–13275. [PubMed]

Wu Z. Viisainen K. Hemminki E. Determinants of high sex ratio among newborns: a cohort study from rural Anhui province, China. Reproductive Health Matters. 2006;14:172–180. [PubMed]

Friedman SH. Horwitz SM. Resnick PJ. Child murder by mothers: a critical analysis of the current state of knowledge and a research agenda. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1578–1587. [PubMed]

Alder C. Polk K. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. Child victims of homicide.

Alder CM. Baker J. Maternal filicide: more than one story to be told. Women and Criminal Justice. 1997;9:15–39.

Bourget D. Gagne P. Maternal filicide in Quebec. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30:345–351. [PubMed]

Bourget D. Bradford JM. Homicidal parents. Can J Psychiatry. 1990;35:233–238. [PubMed]

Cheung PTK. Maternal filicide in Hong Kong, 1971-1985. Med Sci Law. 1986;26:185–192. [PubMed]

Daly M. Wilson M. Killing children: parental homicide in the modern west. In: Daly M, Wilson M, editors.Homicide. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1988. pp. 61–93.

Dean PJ. Child homicide and infanticide in New Zealand. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2004;27:339–348. [PubMed]

Friedman SH. Hrouda DR. Holden CE, et al. Child murder committed by severely mentally ill mothers: an examination of mothers found not guilty by reason of insanity. J Forensic Sci. 2005;50:1466–1471. [PubMed]

Friedman SH. Hrouda DR. Holden CE, et al. Filicide-suicide: common factors among parents who kill their children and themselves. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33:496–504. [PubMed]

Gauthier DK. Chaudoir NK. Forsyth CJ. A sociological analysis of maternal infanticide in the United States 1984-1996. Deviant Behavior.2003;24:393–405.

Haapasalo J. Petaja S. Mothers who killed or attempted to kill their child: life circumstances, childhood abuse, and types of killing.Violence Vict. 1999;14:219–239. [PubMed]

Holden CE. Burland AS. Lemmen CA. Insanity and filicide: women who murder their children. New Directions for Mental Health Services.1996;69:25–34. [PubMed]

Husain A. Daniel A. A comparative study of filicidal and abusive mothers. Can J Psychiatry. 1984;29:596–598.[PubMed]

Karakus M. Ince H. Ince N, et al. Filicide cases in Turkey, 1995- 2000. Croat Med J. 2003;44:592–595. [PubMed]

Korbin JE. Incarcerated mothers’ perceptions and interpretations of their fatally maltreated children. Child Abuse Negl. 1987;11:397–407. [PubMed]

Korbin JE. Childhood histories of women imprisoned for fatal child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl.1986;10:331–338. [PubMed]

Korbin JE. Fatal maltreatment by mothers: a proposed framework. Child Abuse Negl. 1989;13:481–489.[PubMed]

Korbin JE. ‘Good mothers’, ‘babykillers’, and fatal child maltreatment. In: Scheper-Hughes N, Sargent C, editors.Small wars: the cultural politics of childhood. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1998. pp. 253–276.

Laporte L. Poulin B. Marleau J, et al. Filicidal women: jail or psychiatric ward?Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48:94–109.[PubMed]

Lewis CF. Baranoski MV. Buchanan JA, et al. Factors associated with weapon use in maternal filicide. J Forensic Sci. 1998;43:613–618.[PubMed]

Lewis CF. Bunce SC. Filicidal mothers and the impact of psychosis on maternal filicide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2003;31:459–470.[PubMed]

McKee GR. Shea SJ. Mogy RB, et al. MMPI-2 profiles of filicidal, mariticidal, and homicidal women. J Clin Psychol. 2001;57:367–374.[PubMed]

McGrath PG. Maternal filicide in Broadmoor Hospital. J Forensic Psychiatry. 1992;3:271–297.

Marks MN. Kumar R. Infanticide in Scotland. Med Sci Law. 1996;36:201–204.

Meszaros K. Fisher-Danzinger D. Extended suicide attempt: psychopathology, personality and risk factors. Psychopathology. 2000;33:5–10. [PubMed]

Meyer CL. Oberman M. New York: New York University Press; 2001. Mothers who kill their children: understanding the acts of moms from Susan Smith to the “Prom Mom”.

Oberman M. Mothers who kill: coming to terms with modern American infanticide. American Criminal Law Review. 1996;34:2–109.

Pritchard C. Bagley C. Suicide and murder in child murderers and child sexual abusers. J Forensic Psychiatry.2001;12:269–286.

Rouge-Maillart N. Jousset N, et al. Women who kill their children. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2005;26:320–326.[PubMed]

Sakuta T. Saito S. A socio-medical study on 71 cases of infanticide in Japan. Keio J Med. 1981;30:155–168.[PubMed]

Silverman RA. Kennedy LW. Women who kill their children. Violence Vict. 1988;3:113–127. [PubMed]

Smithey M. Maternal infanticide and modern motherhood. Criminal Justice. 2001;13:65–83.

Smithey M. Infant homicide at the hands of mothers: toward a sociological perspective. Deviant Behavior.1997;18:255–272.

Somander LK. Rammer LM. Intra- and extra-familial child homicide in Sweden 1971-1980. Child Abuse Negl.1991;15:45–55. [PubMed]

Stanton J. Simpson A. Wouldes T. A qualitative study of filicide by mentally ill mothers. Child Abuse Negl.2000;24:1451–1460. [PubMed]

Stone MH. Steinmeyer E. Dreher J, et al. Infanticide in female forensic patients: the view from the evolutionary standpoint. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005;11:35–45. [PubMed]

Vanamo T. Kauppo A. Karkola K, et al. Intra-familial child homicide in Finland 1970-1994: incidence, causes of death and demographic characteristics. Forensic Sci Int. 2001;117:199–204. [PubMed]

Wallace A. Sydney: New South Wales Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research; 1986. Homicide: the social reality.

Weisheit RA. When mothers kill their children. Soc Sci J. 1986;23:439–448.

Wilczynski A. London: Oxford University Press/ Greenwich Medical Media; 1997. Child homicide.

Xie L. Yamagami A. How much of child murder in Japan is caused by mentally disordered mothers? Intern Med J. 1995;2:309–313.

Nock MK. Marzuk PM. Murder-suicide: phenomenology and clinical implications. In: Jacobs DG, editor. Guide to suicide assessment and intervention. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1999. pp. 188–209.

Appleby L. Suicidal behaviour in childbearing women. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996;8:107–115.

Schalekamp RJ. Maternal filicide-suicide from a suicide perspective: assessing ideation. www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/ homicide/children.htm.

Jennings KD. Ross S. Popper S, et al. Thoughts of harming infants in depressed and nondepressed mothers. J Affect Disord. 1999;54:21–28.[PubMed]

Levitzky S. Cooper R. Infant colic syndrome: maternal fantasies of aggression and infanticide. Clin Pediatr.2000;39:395–400.

Chandra PS. Venkatasubramanian G. Thomas T. Infanticidal ideas and infanticidal behavior in Indian women with severe postpartum psychiatric disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190:457–461. [PubMed]

Friedman SH. Sorrentino RM. Stankowski JE, et al. Mothers with thoughts of murder: psychiatric patterns of inquiry. Presented at the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting.

Mendlowicz MV. Rapaport MH. Mecler K, et al. A case-control study on the socio-demographic characteristics of 53 neonaticidal mothers. Int J Law Psychiatry. 1998;21:209–219. [PubMed]

d’Orban PT. Women who kill their children. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:560–571. [PubMed]

Coughlin A. Excusing women. 82 Cal L Rev. 1994;1:6.

Guileyardo JM. Prahlow JA. Barnard JJ. Familial filicide and filicide classification. Am J Forensic Med Pathol.1999;20:286–292.[PubMed]

Chandra PS. Bhargavaraman RP. Raghunandan VN, et al. Delusions related to infant and their association with mother-infant interactions in postpartum psychotic disorders. Arch Women Ment Health. 2006;9:285–288.

Cox JL. Holden JM. Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. [PubMed]

Ryan D. Milis L. Misri N. Depression during pregnancy. Can Fam Physician. 2005;51:1087–1093. [PubMed]

Altshuler LL. Hendrick V. Cohen LS. Course of mood and anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl. 2):29–33. [PubMed]

McCleary R. Chew KSY. Winter is the infanticide season. Homicide Studies. 2002;6:228–239.

Palermo MT. Preventing filicide in families with autistic children. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol.2003;47:47–57. [PubMed]

LEGAL NOTICE

©David B. Knechel. All Rights Reserved. No portion of this site can be reproduced in it's entirety or in part without expressed written permission by the owner/administrator of this site in accordance with the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. Section 512(c)(3) of the U.S. Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. §512(c)(3). The charges against defendants are mere accusations and the subjects are presumed innocent until found guilty in a court of law.

LEGAL NOTICE

©David B. Knechel. All Rights Reserved. No portion of this site can be reproduced in it's entirety or in part without expressed written permission by the owner/administrator of this site in accordance with the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. Section 512(c)(3) of the U.S. Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. §512(c)(3). The charges against defendants are mere accusations and the subjects are presumed innocent until found guilty in a court of law.

Reader Comments