CROSS CREEK

Cross Creek was home to Pulitzer Prize winning author Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings for 25 years, from 1928 until her death in 1953. It’s an enchanting little hamlet you could easily picture in your head; a picturesque place with a babbling brook and quaint bridge that spans it. There’s none of the clutter you’d expect from a large town — no traffic lights, no horns blaring, and nothing to hear other than the faint sounds of birds cheerfully chirping in nearby trees. Yes, that would be a very good description. It’s a secluded community that epitomizes Old Florida. This year, though, there’s no babble in the brook that separates Orange Lake from Little Lochloosa Lake. A dry winter is to blame. Not long ago, down at th’ crick, you could catch a cooter wit a cane pole.

Of her adopted town, Rawlings often wrote of the harmony between the wind and rain, the sun and seasons, the seeds and, above all else, time. Once you enter Cross Creek, you become a part of its mystique. There’s a feeling of calm that fills the heart and you’re beckoned back to an era of bygone years, listening to Bing Crosby on an RCA Gramophone instead of Kanye West on an iPod; when the country doctor still made house calls and he’d gladly take a freshly baked pecan pie as payment. Those were the days…

Of her adopted town, Rawlings often wrote of the harmony between the wind and rain, the sun and seasons, the seeds and, above all else, time. Once you enter Cross Creek, you become a part of its mystique. There’s a feeling of calm that fills the heart and you’re beckoned back to an era of bygone years, listening to Bing Crosby on an RCA Gramophone instead of Kanye West on an iPod; when the country doctor still made house calls and he’d gladly take a freshly baked pecan pie as payment. Those were the days…

Most of Rawlings’ work centered around rural central and north Florida, including Cross Creek, and in 1938, she found immense success with The Yearling, the story of a boy, his pet deer and his relationship with his father. Until it was published, most literary critics considered her to be a regional writer, but she disagreed. There’s more to writing than that. “Don’t make a novel about them unless they have a larger meaning than just quaintness.”

Rawlings grew up in the Brookland section of Washington, DC, and attended the University of Wisconsin, but years of living in Cross Creek transformed her. She felt a profound connection to the area and the land. While the locals were wary at first, they soon warmed up and told stories of their own experiences, which she diligently wrote down in notebook after notebook, along with descriptions of plants and animals, recipes, and examples of southern dialects.

The following 2 pictures are of Rawling’s house.

While doing research for The Yearling, Rawlings went into nearby scrub forests and spent several weeks with a Florida Cracker, hunting, fishing, and going on a couple of bear hunts. She convinced him that she was interested in the old customs, which was the truth. Trust me, you will never win over a Cracker by lying, and you cannot be a cracker unless you was born in the state. Crackers either accept you or they don’t and there ain’t no in between.

According to Elizabeth Silverthorne, who wrote Rawlings’ biography Sojourner at Cross Creek, Rawlings received the acceptance of her neighbors because she learned quickly about their system of morals and values. For instance, neighbors helped pick pecans from her trees in exchange for enough of the crop to last them through the winter. She became interweaved with local folks.

In every small town, you’ll find neighbors who gaze out front windows through cracks in the curtains to see what others in the community are doing. Cross Creek was no different during Rawlings’ time. Interestingly, she based a lot of her fictional characters on people who lived in the town and surrounding areas, and because of it, resentments arose, despite the fact that she never once used anyone’s full name.

Zelma Cason was, at one time, a very close friend of the author’s and her first in Cross Creek. She was, that is, until she felt the sting of Rawlings’ pen in a portrayal of her in the book Cross Creek:

“Zelma is an ageless spinster resembling an angry and efficient canary. She manages her orange grove and as much of the village a county as needs management or will submit to it. I cannot decide whether she should have been a man or a mother. She combines the more violent characteristics of both and those who ask for or accept her ministrations think nothing at being cursed loudly at the very instant of being tenderly fed, clothed, nursed, or guided through their troubles.”

Cason took offense, so in 1943 she sued Rawlings for $100,000 for invasion of privacy. The trial became a spectacle as the struggle between the right of privacy and free speech ensued in open court, with Cason arguing that Rawlings did not have the right to publish a description of her without permission, and Rawlings countering with free speech. Interestingly, no Florida court had ever heard an invasion of privacy case prior to this one, and laws on libel were too ambiguous in those days. (Florida started its tradition of openness back in 1909 with the passage of Chapter 119 of the Florida Statutes or the Public Records Law.)

Cason’s attorney, Kate Walton, was one of the first females to represent a client during a time when women weren’t allowed to serve on juries in the state. Sigsby Scruggs was a well-known, crafty, cracker attorney hired by Rawlings, along with Jacksonville attorney Philip May. As much as we watched the Casey Anthony trial unfold during the course of three years, the world’s eyes were on the little Florida town of Cross Creek while WWII raged on. Rawlings’ husband at the time and until her death was Norton Baskin. “I haven’t seen people around here so stirred up about anything since that two-headed calf was born over to Island Grove,” he said. [1]

From The St. Augustine Record, Monday, April 19, 2010:

The trial, held in Gainesville, drew state reporters and noisy crowds. The original trial and the appeals that followed took several years.

In the end it was a “bloody stalemate,” writes Townsend. [Billy Townsend’s great-aunt is the late Kate Walton.]

The jury in Alachua County stood by Rawlings and “laughed Zelma and Aunt Katie and J.V. out of court. It took them 28 minutes to find for Marjorie.”

But in 1947 the Florida Supreme Court overturned the verdict. It “both established the right of privacy exists in Florida and proved that Marjorie invaded Zelma’s privacy in ‘Cross Creek,’” he writes.

But the court limited damages to $1 plus attorney fees. Zelma had been “wronged, but not harmed.”

Cason couldn’t prove she’d suffered mental anguish or that Rawlings acted with malice. Rawlings failed to convince the judges that they were harming an author’s ability to write.

“They both thought they had lost,” Townsend said.

Before they died, Cason and Rawlings became friends of sorts once again.

Cason claimed that the lawyers made her do it. Townsend thinks Cason came to Kate Walton to start the suit rather than lawyers approaching her. But, now, all the people who knew for sure are gone.

As we looked over part of Rawlings’ property, Nika1 informed me that she was supposed to be buried in a different cemetery when she died, but in a twist of irony, there was a mix up and she ended up in the same cemetery as her one-time friend, Zelma, who had bought plots there earlier. When Cason died in 1963, she was buried 50 feet away from Rawlings. Quite literally, they followed each other to their graves.

It was now after 5:00 pm in Cross Creek, and as the lesson in history wound down and the sun edged closer to the horizon, Nika1 and I realized it was time to eat, and reservations had already been made at The Yearling Restaurant, a stone’s throw from Rawlings’ house. From the outside, the restaurant isn’t anything fancy to look at. As a matter of fact, there’s nothing at all pretentious about it. Looking at it from the front, it doesn’t look very big, either, but once you get inside, it’s almost cavernous. Our host led us to a good-sized back room where, later, two musicians sang and played their instruments. Our waitress for the evening was a delightful young lady named Leslie. You haven’t lived until you’ve eaten fried green tomatoes, and there are none finer than what we were served. For entrees, Nika1 ordered fried fish and I got fried gator tail. Yes, you heard that right. I had eaten it before, but none was as tender as this go around.

It was now after 5:00 pm in Cross Creek, and as the lesson in history wound down and the sun edged closer to the horizon, Nika1 and I realized it was time to eat, and reservations had already been made at The Yearling Restaurant, a stone’s throw from Rawlings’ house. From the outside, the restaurant isn’t anything fancy to look at. As a matter of fact, there’s nothing at all pretentious about it. Looking at it from the front, it doesn’t look very big, either, but once you get inside, it’s almost cavernous. Our host led us to a good-sized back room where, later, two musicians sang and played their instruments. Our waitress for the evening was a delightful young lady named Leslie. You haven’t lived until you’ve eaten fried green tomatoes, and there are none finer than what we were served. For entrees, Nika1 ordered fried fish and I got fried gator tail. Yes, you heard that right. I had eaten it before, but none was as tender as this go around.

When you’re inside the restaurant, it’s really a cozy, homey kind of place. It’s precisely what you’d expect in Cross Creek — comfort food, and I must say, the sour orange pie for dessert was fantastic!

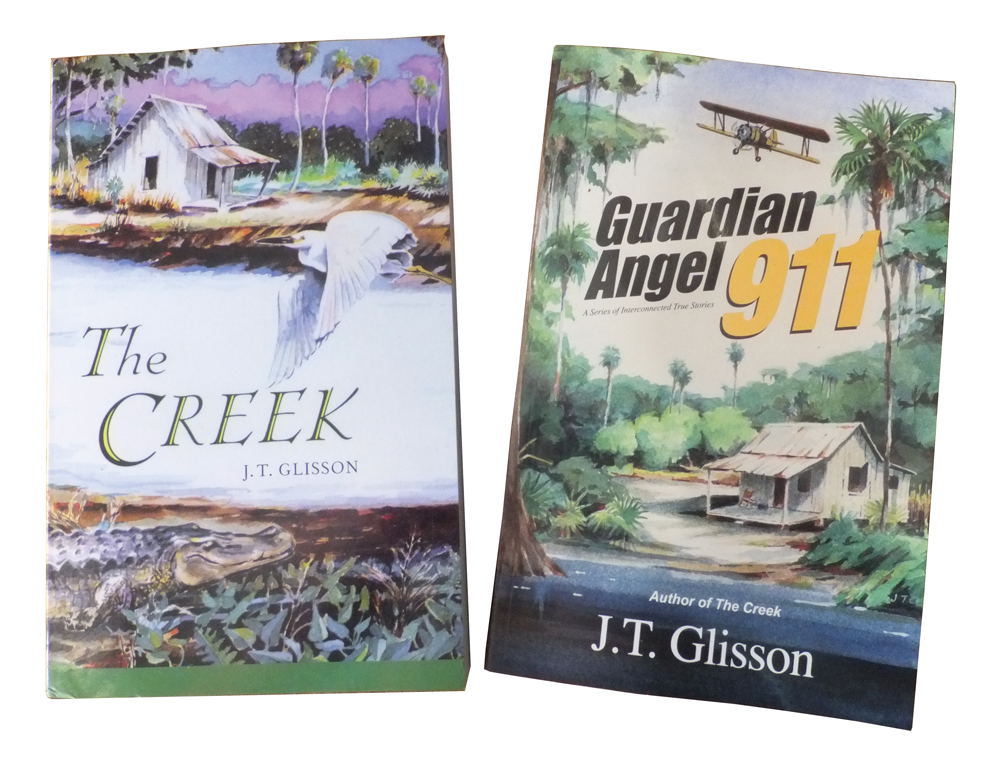

While we sat waiting for our food, we talked about the area; not just Cross Creek, but also about Alachua County, including where Nika1 resides. It’s amazing how many people know each other even when they live 20 miles apart. It’s a close-knit community, so when she told me the story about the history of the restaurant and one of the area’s most colorful gentlemen, I found myself captivated by what she was saying. One of her close neighbors was characterized in The Yearling. In the book, he was the crippled boy. In real life, his name is J.T. Glisson, but once you know him, his name is Jake. When the original owners opened the restaurant in 1952, they commissioned Jake to paint a picture of a yearling — one that could have been the one portrayed in the book. He did, and there it hung for 40 years. The original owners closed the restaurant in 1992 and it reopened in 2002 under new ownership. When it closed in 1992, Jake asked if he could get his painting back. The owner honored his request, and today, it proudly hangs in Nika1’s house.

Jake is in his 80s now, but he’s not just a painter, he’s an author; a writer of books. I think there’s something in the air up there in Alachua County. I sense it’s where a lot of creative juices flow, and they once babbled through Cross Creek. The world is a wonderful place, and the legacy of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings lives on. Why? Because she didn’t just write The Yearling, she lived it…

Jake is in his 80s now, but he’s not just a painter, he’s an author; a writer of books. I think there’s something in the air up there in Alachua County. I sense it’s where a lot of creative juices flow, and they once babbled through Cross Creek. The world is a wonderful place, and the legacy of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings lives on. Why? Because she didn’t just write The Yearling, she lived it…

“Enchantment lies in different things for each of us. For me, it is in this: to step out of the bright sunlight into the shade of orange trees; to walk under the arched canopy of their jade like leaves; to see the long aisles of lichened trunks stretch ahead in a geometric rhythm; to feel the mystery of a seclusion that yet has shafts of light striking through it. This is the essence of an ancient and secret magic.”

— Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

(See: The Yearling, a 1946 movie starring Gergory Peck and Jane Wyman)

Next: My Trip to Gainesville, Part 4 — Micanopy, the oldest inland town in Florida.